So how did this instrument get to the Americas and become associated with a particularly white, rural musical form? What can its history tell us about the musical landscape of the United States? What are Black artists today doing to reclaim the banjo’s heritage?

Let’s start at the beginning…

Early Banjo History

African Spiked-Gourds and the Akongting

Spiked-lutes spread across West Africa and took on a life and sound of their own. There are more than 60 unique types of plucked gourd-lute instruments found throughout West Africa. These instruments became culturally significant as highly-skilled storytellers, musicians, and poets called Griots often incorporated the lute into their storytelling and poetry, and people produced their own instruments and developed their own styles of playing.

It was this family of instruments that enslaved Africans remembered when they themselves were forcibly brought to the Americas.

It is important to note that these West African gourd-lutes have been evolving in their own culture and history, and it is likely impossible to know just which one is the direct ancestor of the banjo – it probably has DNA from many of them. Other closely-related instruments include the Frafra koliko (Ghana), the Kotokoli (also Tem or Temba) lawa (Togo, Benin and Ghana), the Gwari kaburu (Nigeria), and the Hausa gurmi, komo, komsa and wase (Nigeria, Niger, Ghana).

Below, you can see Laemouahuma Daniel Jatta play his father’s akonting.

The Banjo in the New World

Somehow, stripped of freedom and possessions, enslaved Africans ensured that the lute-gourd instruments survived the Middle Passage. Instruments like this Jamaican Creole Bania (below) began appearing across plantations and port-towns of the Caribbean and American South. The earliest banjos discovered in Haiti date back to the early 1600s.

It was within the tumultuous – and forced – synchronization of several African cultures, musics, religions, and ideas in the Caribbean that the banjo as we understand it likely emerged. In the 1600s in the Caribbean, millions of people from all over Africa who spoke different languages and came from different cultures had to learn how to communicate with each other, and one of the best ways to communicate was through music.

It was during this time that European outsiders began commenting on these new musical styles, calling the gourd-lute instruments by names like “bangie, banza, bonjaw, banjer or banjar.” The origin of these names is still unclear, but it’s possible they were derivative of “bang julo,” the Mandinka term for the rope fiber that was potentially used in making early versions of the akonting (the capital of Gambia, Banjul, also takes its name from this term).

In an interview with Afropop, Rhiannon Giddens – one of the premier banjoists of our time, committed to tracing the history of the instrument and music – says:

“I like to call the banjo African-American (and by American I mean the whole of the Americas, not just the U.S.). Because you have Africa… with huge variations in people, cultures, musics… but the fact of the matter is that when people were brought to the New World, they maintained their own cultural label and heritage as much as they could. But a different culture starts to form, because it has to. People are surviving. The banjo is from that culture. It is not a Guinean instrument, it is not a Gambian instrument, it is an African-American instrument. It is born out of a lot of different people coming together and creating a way to survive… It has all of these different pieces of Africa in it, but it is also something that does not exist in Africa. It is what an African-American culture is.”

We have oral and visual histories of Black communities in the South and North that specifically mention four- and five-string banjo-like instruments. We know that enslaved people played the banjo – because notices for escaped slaves specifically mention their musical abilities. There are written records of parties at plantations in the South that mention non-white bands.

Below is an image of The Old Plantation (1785 – 1795), the earliest known American painting to picture a banjo-like instrument; thought to depict a plantation in South Carolina.

By the 19th century, banjos were found in the American North, West, South, and, of course, remained predominant in the Caribbean. Banjos became part of mento music in Jamaica, a forefather of reggae. It became part of calypso music in Trinidad and Tobago. It rang out in Haiti and throughout the rest of the Afro-Caribbean world. This influence changed the style of banjo playing throughout the United States.

So how did the banjo and its audience move up the Mississippi and become associated with a white, rural style of music?

The answer lies in a piece of America’s racist past: minstrel shows.

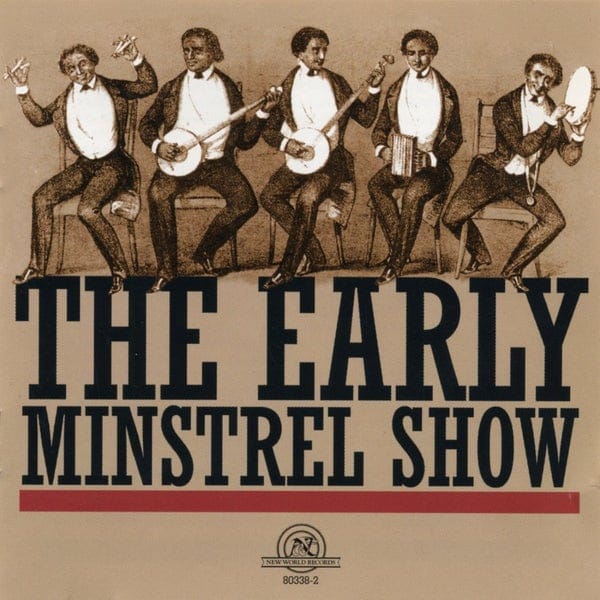

Minstrel Shows

The earliest minstrel shows were staged by white male traveling musicians who, with their faces painted black, caricatured the singing and dancing of slaves. It was through minstrel shows that the music and banjo came to American stages, but this time at the hands of white performers, typically in blackface and featuring exorbitant racism. The shows were immensely popular.

The impact of these shows was immense, both on the history and prevalence of racism in America, and also on the banjo’s popularity and history. The so-called “father” of the blackface show was Thomas Dartmouth Rice, popularly known as “Jim Crow.” The U.S. system of racial laws and segregation that lasted until the 1960s derived its name from his fame.

The popularity of minstrel shows also came with commercial production. The banjo adopted its current look with a rounded body, tight skin like a drum, and metal strings and frets. It became cheaper to make and buy, and louder. Then came the minstrel bands, which were typically formed by banjo, fiddle, tambourine, and percussion instruments like bones.

Musicians of all sorts began transcribing – and buying – popular minstrel show tune sheet music, and banjo music began spreading to white communities across the U.S.

This marked the first time that these folk tunes were written down and distributed en masse, albeit in classical European notation. It is impossible to uncouple the musical and historical impact of the minstrel shows from their racist history. Minstrel shows helped preserve many Black folk tunes and a particularly Black style of playing – just as it featured racist depictions of the Black musicians whose music was being stolen. White musicians started picking up the banjo and learning a common language of music, played on a quickly-standardizing banjo.

Class-based cultural-crossover

It is important to note that cultural-crossover occurred in other forms, too.

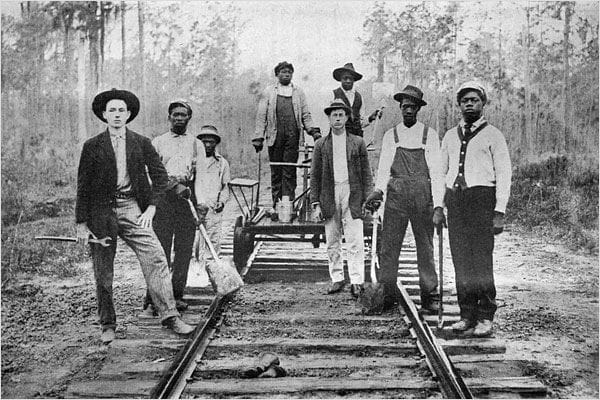

Prior to and in addition to minstrelsy, white, mostly non-slave owning, mountain musicians learned the instrument from the Black banjo players they lived with in the Appalachians – and this cultural-crossover left lasting marks on Appalachian phonics. This was usually a class-based cultural phenomenon. Black railroad and steamboat workers, who often migrated to Appalachia from the Deep South for jobs on the railroad, taught the banjo to their fellow white laymen who in turn taught a new generation of banjo players. A distinctive musical style and sound emerged from these working relationships.

However, it was minstrelsy and the minstrel bands that firmly cemented the banjo into white American consciousness and mainstream music.

America’s banjo-craze

Thanks to the popularity of the minstrel shows, America entered a “banjo-craze” in the late 1800s. Banjo music was everywhere – and the banjo spanned all types of music. It was seen as a break from the European culture that predominated America previously and celebrated by the likes of Whitman and Twain. Orchestras in Carnegie Hall began featuring the banjo. Women-led clubs began teaching their members the banjo.

Again, Rhiannon Giddens brilliantly explains the craze: “One of the reasons why it has such a wide reach is the same reason that Black American music has such a wide reach. Because what Black culture does in the New World is that it synthesizes itself, and then it synthesizes aspects of European culture and it creates something new. Then there’s this conversation between Black American culture and the European culture around it, that continues on with whatever art form it is that has been formed. But it starts within that cocoon of innovation within Black culture. When that goes out, people recognize the innovation… and people also recognize pieces of it.”

Rewriting Black History

By the turn of the 20th century, the Black history of the banjo was being rewritten in full. As Black Southerners were increasingly displaced and moved North in what would become known as the “Great Migration,” the rhythm of daily life and cultural practice shifted – away from the “old” music of the banjo and toward the newer, fresher jazz and blues being performed in most major cities. Electric guitars took over for the banjo in jazz ensembles as recording techniques improved.

As the racial composition of the South was changing, the recording industry reared its head. Trying to sell records, companies started reinforcing a segregation of music. Blues became music solely for Black folks – recorded and marketed to Black Americans. Banjo music and string bands became “hillbilly music,” marketed to rural, white Appalachia and the South. This segregation and marketization of recorded music – music that is historically solidified because it is recorded – reinforced the idea of banjo folk music being made by and for white people. This was only furthered by the media campaigns, which promoted the idea of banjo players being white folks like the Beverly Hillbillies.

For example, Bill Monroe named Arnold Shultz, his Black neighbor who played in string bands, as a huge influence on his playing style. But even though the artists themselves recognized the banjo’s history, bluegrass stages were dominated by white musicians and audiences.

This continued into the modern era – with banjo music fixedly considered to be a “white” art form.

Reclaiming the Black banjo legacy

In the last 15 years, there has been a renewed effort by Black artists like Rhiannon Giddens and Hubby Jenkins from bands like the Carolina Chocolate Drops to reclaim and represent the legacy of Black string bands and Black banjo players. These artists release fantastic music, worthy of several listens.

A list compiled by Jake Blount, a banjo player and fiddler working to uncover the truths of the Black banjo legacy, is an excellent place to start your listening. However, it is by no means exhaustive of the fantastic Black artistry and banjo playing currently out there:

- Fiddlin’ Earl White

- The Carolina Chocolate Drops

- Jake Blount

- Our Native Daughters

- Tray Wellington

- Ben Hunter & Joe Seamons

- The Ebony Hillbillies

- Kaïa Kater

- Jerron “Blind Boy” Paxton

What can we learn from the Banjo’s complicated past?

The banjo is by no means the only example of Black art and excellence being co-opted, commercialized, and marketed to and by a white audience. It is merely representative of a larger feature of American musical history.

African American folk music has been extremely influential on the musical landscape of America. Features of Black folk music like the use of call-and-response, storytelling, polyrhythm, and melody still play out in today’s music. Rap music makes heavy use of call-and-response, syncopation, and storytelling; blues and jazz came directly out of African American stories, struggles, musical improvisation, and African-based polyrhythm. Characteristics of many of the genres we listen to today can be credited to Black folk music.

For so many years, old-time, bluegrass, banjo music, and stringband music was made mostly by Black folks, occasionally passed along to their white neighbors. Old-time, string music, and bluegrass is not “white” music. There is no all-white American folk music, because there is no all-white American history. And there is certainly no all-white American music history.

It seems fitting to close with this quote from W.E.B. Dubois’ Souls of Black Folk:

“Little of beauty has America given the world save the rude grandeur God himself stamped on her bosom; the human spirit in this new world has expressed itself in vigor and ingenuity rather than in beauty. And so by fateful chance the Negro folk-song—the rhythmic cry of the slave—stands to-day not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side the seas. It has been neglected, it has been, and is, half despised, and above all it has been persistently mistaken and misunderstood; but notwithstanding, it still remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gift of the Negro people.”

Resources/Recordings/History:

The history told in this blog post was not mine, and it was only possible through the efforts of many fabulous musicians, historians, artists, and creatives. If you would like to learn more about the Black history of the banjo, please use and cite these resources as a guide — they helped guide me in this process.

A great place to start is Jake Blount’s website, found here: https://jakeblount.com/

Jake has complied a fantastic list of resources, recordings, and readings on a free google doc on his website. He offers this as a free resource, should you wish to compensate him for this work, he accepts PayPal and Venmo (@jakeblount); or, buy a copy of his recent album Spider Tales.

The IBMA’s Arnold Shultz Fund supports scholarships and activities aimed at increasing participation of people of color in bluegrass music. You can learn more or donate here: https://bluegrassfoundation.org/arnold-shultz-fund/

Another great organization committed to reclaiming the Black history of the banjo can be found here: https://blackbanjoreclamationproject.org/

Consider donating to their efforts.

Other resources I used in the creation of this article are listed here:

https://www.rhiannongiddens.com/about

https://afropop.org/audio-programs/the-black-history-of-the-banjo

https://www.britannica.com/art/minstrel-show

https://sites.duke.edu/banjology/banjo-and-jazz/

https://www.npr.org/2011/08/23/139880625/the-banjos-roots-reconsidered

https://www.folkways.si.edu/

There are many, many resources out there on these musical histories — and even more recordings to listen to! Please check them out and support the artists dedicated to a fantastic instrument and sound.

Thank you for reading this week’s blog!! Please continue to educate yourself on the incredible history of Black phonics and art in this country, and stay tuned to the Front Porch’s blog for more news, articles, information, and announcements.

Interested in learning an instrument? The Front Porch offers individual and group music classes for all ages and skill levels! Sign up for a class with Harold or one of our other amazing teachers today. It’s never too late to start!

Love what The Front Porch does? Learn more about our Roots and Wings outreach program here, and donate to support music education in Charlottesville.

Just looking to listen to some music? Check out our upcoming concerts and events!